Razib Khan on the Genes of Palestinians and European Jews

They both were Canaanites, speaking Hebrew, once upon a time.

In More than kin, less than kind: Jews and Palestinians as Canaanite cousins, Razib Khan ends with this telling read of the genes of European Jews and Palestinians:

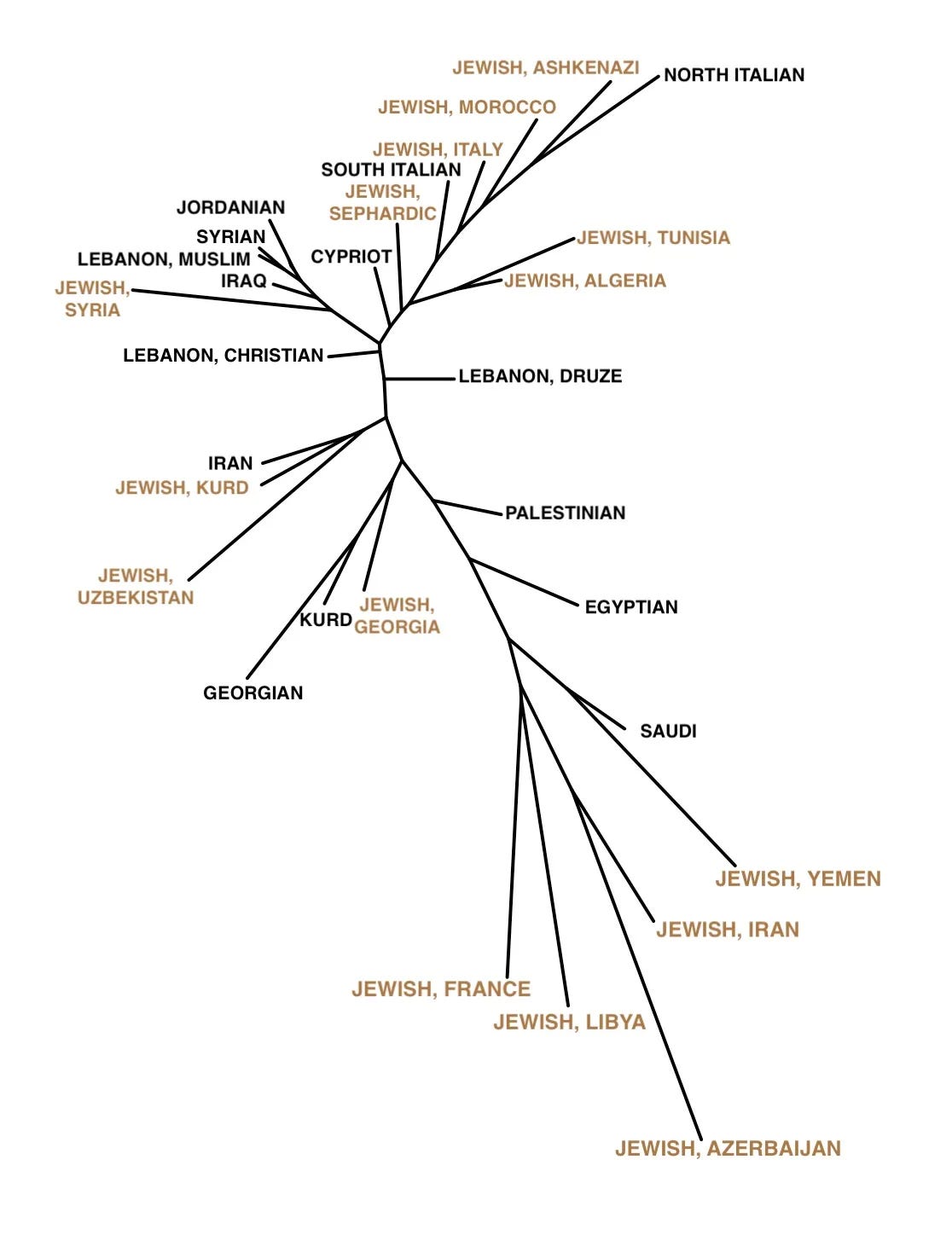

It’s a bittersweet coda to the Jewish return to Palestine that both they and the native Arabs descend from the same Levantine populations, meaning it is a reunion of kin. The ancestors of Jews and Arabs both worshiped one god, promulgated ethical monotheism, and would proselytize it throughout the wider world. During the time of the first (66-73 AD) and second rebellions (132-136 AD) against Rome, Palestine was a substantially Jewish province, albeit with large minorities of pagans and Samaritans. With the gradual conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity beginning in the 4th century AD, most of the region’s population adopted the new religion. But these people had previously been Jews. With the arrival of Islam, the religion of the populace changed again (though ironically, the Arabic word for God, Allah, is cognate with the West Semitic El, also one of the Hebrew god’s names). The culture and identity of ancestors of the Arab Palestinians evolved and mutated over the generations, but the bulk of their roots have always been in the region, going back to Roman-era Jews, and before that, pagan Canaanites and ultimately Natufian farmers and foragers.

The Jews’ return from Europe in larger numbers in the early 20th century was the homecoming of people who had evolved and changed genetically via the assimilation of neighbors drawn from gentile majorities, in particular gentile women who followed in Ruth’s footsteps. But these people’s self-conception was firmly rooted in Middle Eastern Judaism, with a religious life that centered around the Babylonian Talmud. Though only a minority of Ashkenazi ancestry is Levantine, their continued adherence to a Jewish identity goes back to Jacob and his sons. Their own identity is the identity of these ancient Levantine patriarchs, liminal figures at the threshold of recorded history. In contrast, while Palestinian Muslims are mostly Levantine in their blood and most of their ancestors were certainly likely to have been Jewish in 300 AD, their meme package has drawn them away from this ancestral birthright. And despite the native Palestinian biological kinship with the Ashkenazi migrants, a line of ancestry converging back into one less than 2,000 years ago, the two groups were to become the late 20th and early 21st centuries’ ultimate antagonists, their very names, when joined, bywords for conflict, strife and irreconcilable interests.

Some stories don’t have tidy, happy endings. Genetics and history are complicated, but not nearly as complicated as geopolitics and international relations. Human enmity is powerful enough to sunder even the deepest and most ancient bonds of blood. My misgivings about weighing in on the quantifiable genetic aspects of this question remain. Our god-like 21st-century capabilities in genomics might let us illuminate secondary questions of history and genetics deep in our past with infinite impartiality and precision. But outside the lab, our species tends to remain stubbornly like siblings of a biblical vintage, or Shakespearean brother kings, locked in eternal strife and enmity. Data or no, meaningful consensus about who we are and how to coexist will no doubt prove elusive and the path forward no less clouded or perilous than when we set out.

There was one line that also stood out for me:

As my friend Taylor Capito likes to say, Italians don’t look like Jews, Jews look like Italians.