On The Radar: Yesterday's Logic

Peter Drucker | Democrat's Dilemma | On Nato | Japan’s View | Scions of Sahul

The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence — it’s acting with yesterday’s logic.

| Peter Drucker

Democrats’s Dilemma

In Democrats Don’t Have a Nominee Until Delegates Say So, Daniel Schlozman lays out the actual Democratic party rules about how the convention chooses the candidate:

There are to be around 3,934 pledged delegates at the convention from every state and territory and Democrats Abroad. Those delegates are, save for a tiny smattering of uncommitted delegates and seven who are committed to Dean Phillips and Jason Palmer, Biden delegates. That means their delegate slots have been awarded based on Mr. Biden’s performance in party primaries. They have received the approval of the Biden campaign and pledged to support the president on the first presidential ballot.

They are also required to attest that they are “bona fide Democrats who are faithful to the interests, welfare and success of the Democratic Party.” Thanks to the party’s strict affirmative action and gender balance rules, they are a notably diverse group — far more so than most other elites in American life.

The delegates are pledged, not bound. Note this from the party’s official rules: “All delegates to the national convention pledged to a presidential candidate shall in all good conscience reflect the sentiments of those who elected them.” That is a pledge of fealty to Democratic voters and to those voters’ conscience as stewards of the democratic process — not to a candidate.

It gives delegates a measure of autonomy to respond to new circumstances, especially in the months between the primary in a given state or territory — the “first determining step,” in the language of party rules — and the national convention.

In addition to the pledged delegates, about 739 party leaders and elected officials — so-called superdelegates — each have a vote on all procedural matters, including the rules of the convention and the platform, as well as the presidential nomination if no candidate has a majority on the first ballot (they can’t vote on the first ballot). These superdelegates — members of the Democratic National Committee, members of Congress, governors, big-city mayors — are there to subject candidates to scrutiny. These party leaders and elected officials come to the table with unique expertise — they see politics up close and have to suffer the consequences if a flawed nominee drags down the ticket. They are there to protect the party’s broader interests rather than the narrow interests of any single candidate.

Here is how the nomination for president at the national convention works: By a date just before the convention, a group of delegates may place the name of a Democratic candidate into nomination. Delegates may also vote “for the candidate of their choice whether or not the name of such candidate was placed in nomination,” and their votes are then tallied, assuming they voted for a bona fide Democrat who has agreed to be a presidential candidate.

This is all to say that the delegates to the national convention have the power — if they wield the rules carefully and act collectively — to choose the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024. Superdelegates ought to start saying publicly, now, that they are aware the convention can pick a different nominee. And pledged delegates, often further from national headlines than big donors but closer to realities on the ground, need not wait to start making their opinions known.

So, it’s not Joe’s decision: it’s the delegates, but if and only if they read the rules before showing up at the convention.

And, of course, the assassination attempt on Trump has sent these discussions into a tailspin.

On Nato

Lily Lynch, in Why Nato fears for its future, points out that Biden’s frailty makes Nato look frail, too.

As Biden stumbled through his final, possibly terminal, press conference, he did manage to make one clear point: that Trump and his ilk were a threat to Nato. Why the average American voter should care as much as those assembled in Washington, he did not say. And while the eyes of the world watched this very public demonstration of his vulnerability, it was clear that the future of Nato and the entire transatlantic order will be determined by who is elected president in November. The summit that was supposed to be a celebration of the alliance’s stability and longevity was instead a testament to its frailty.

Subscribe to have stoweboyd.io missives appear in your email inbox.

Japan’s View

h/t to Ian Bremmer. One comment on the X.com thread: ‘where’s the guns?’

And regarding the Mac v PC contrast: Windows 11 is so bad, lots of Republicans are switching.

Scions of Sahul

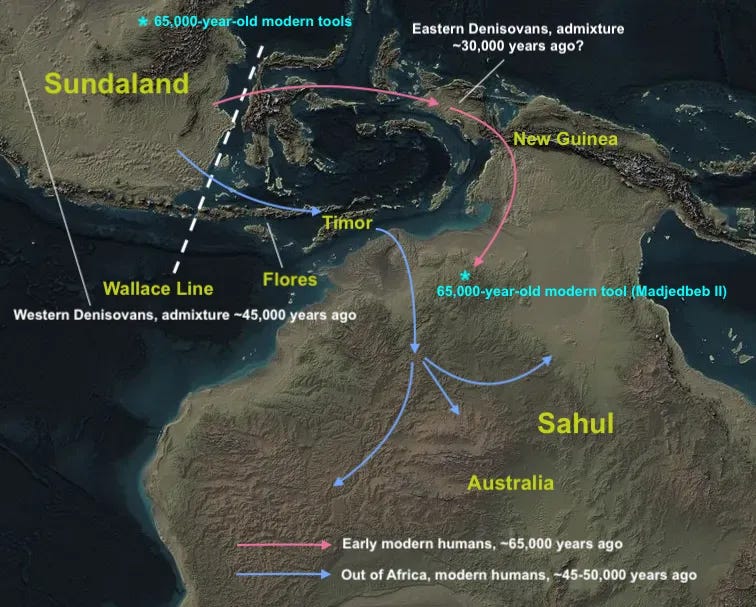

Sahul is the name that paleoanthropologists and geographers assign to the historical landmass that today — now that sea level is lower — includes New Guinea and Australia.

This map captures a great deal of information. The arrows represent the travel of humans tens of thousands of years ago, leading to the settlement of these lands, and their occupation until the present day by descendants of those early travelers until the arrival of Europeans a few hundred years ago.

In Scions of Sahul: the steadfast Australian settlers who held off sedentarism for 45,000 years, Razib Khan lays out the genetic and anthropological arguments for the migration and ancestry of the Australo-Papuan peoples, with particular attention to overturning the previous generally accepted timeframes and the inclusion of one admixture of Neanderthal genes (along with almost all other non-African humans) and two admixtures of Desinovan genes. They reached Sahul at least 45,000 years ago.

This is one of the most detailed and fascinating articles I have read in years. That may be because I knew so little about the subject, along with the facts that have been revealed in recent years by genetics and paleoanthropology. For example [emphasis mine]:

Aside from the unexpected fact of their very existence, perhaps the most shocking thing about the Denisovans, first discovered from a single genome in Siberia, is that the modern population with the most detectable ancestry from these prehistoric humans today are Papuans, the indigenous people of New Guinea, 5,500 km from Denisova cave, beyond China, Thailand and Indonesia, in the far-flung lands bridging the Indian and Pacific oceans. Our understanding of the geography of Denisovan admixture into modern populations has seen refinements since 2010, thanks both to two other Denisovan genomes and the massive progress generally in whole-genome sequencing of humans. In 2010, when Denisovans were discovered, on the order of thousands of human genomes had been sequenced; today there are millions. We now know that Denisovan ancestry is found across Asia, with proportions around 0.2% in South Asia, 0.1% in East Asia (and among Amerindians), and pockets of even slightly higher levels in Indonesia. The current best estimate is that 3% of modern Papuan ancestry comes from Denisovans. A similar proportion holds for indigenous Australians and other Melanesians. This is a function of their common ancestry from an ancestral population that mixed with Denisovans and subsequently diversified. Curiously, at 4%, the Negrito people of the Philippines, and in particular the Agata tribe, have the most Denisovan ancestry of any human population, pointing to a distinct, diverged demographic trajectory from the Australo-Melanesian people to their south and east.

But the real payoff from the article is the big picture of the complex genetic divisions and mixings from the time of the ‘out of Africa’ migrations as the background to the specific circumstances of the Australo-Papuan people.

A must-read article for the curious.

One compelling factoid is that Indigenous Australians rejected agriculture for tens of thousands of years, even though they must have known about it (for example, by trading with agriculturalists like Torres Islanders), and despite access to territories in southeast Australia with a perfect climate for it. And no invaders showed up — or survived attempted invasion — to disturb that hunter-gatherer life cycle for as long as 50,000 years.