2024-05-06 Notes | Rewilding, Echolocation

George Monbiot | J. G. Ballard | Wikipedia

I am starting to post daily notes on stoweboyd.io, various materials that come my way through my research. Subscribe to have it appear in your email inbox.

George Monbiot on Rewilding Politics

Complexity tends to be resilient, while simplicity tends to be fragile. | George Monbiot

…

Looking back on George Monbiot’s Rewilding Politics, from 2019, his insights hold true today, and maybe even more so:

Something has changed: not just in the UK and the US, but in many parts of the world. A new politics, funded by oligarchs, built on sophisticated cheating and provocative lies, using dark ads and conspiracy theories on social media, has perfected the art of persuading the poor to vote for the interests of the very rich. We must understand what we are facing, and the new strategies required to resist it.

[…]

At the moment the political model, for almost all parties, is to drive change from the top down. They write a manifesto, that they hope to turn into government policy, which might then be subject to a narrow and feeble consultation, which then leads to legislation, which then leads to change. I believe the best antidote to demagoguery is the opposite process: radical trust. To the greatest extent possible, parties and governments should trust communities to identify their own needs and make their own decisions.

The entire piece is worth reading, or re-reading.

He poses something like a manifesto:

It is time for political rewilding.

When you try to control nature from the top down, you find yourself in a constant battle with it. Conservation groups in this country often seek to treat complex living systems as if they were simple ones. Through intensive management – cutting, grazing and burning – they strive to beat nature into submission until it meets their idea of how it should behave. But ecologies, like all complex systems, are highly dynamic and adaptive, evolving, when allowed, in emergent and unpredictable ways.

Eventually, and inevitably, these attempts at control fail. Nature reserves managed this way tend to lose abundance and diversity, and to require ever more extreme intervention to meet the irrational demands of their stewards. They also become vulnerable. In all systems, complexity tends to be resilient, while simplicity tends to be fragile. Keeping nature in a state of arrested development, in which most of its natural processes and its keystone species (the animals that drive these processes) are missing, makes it highly susceptible to climate breakdown and invasive species. But rewilding – allowing dynamic, spontaneous organisation to reassert itself – can result in a sudden flourishing, often in completely unexpected ways, with a great improvement in resilience.

The same applies to politics. Mainstream politics, controlled by party machines, have sought to reduce the phenomenal complexity of human society into a simple, linear model, that can be controlled from the centre. The political and economic systems they create are simultaneously highly unstable and lacking in dynamism==: susceptible to collapse, as many northern towns can testify, while unable to regenerate themselves. They become vulnerable to the toxic, invasive forces of ethno-nationalism and supremacism.

I wrote about rewilding in business for Webex Ahead: The ecology of work: growing resilient, growing wilder.

Perhaps corporate leaders need to reconsider the ‘business as a machine’ mindset that places optimization of business processes above the agility and flexibility that underlies resilience. Instead of seeking to make the company into the leanest possible linear system—a strategy of reduction—leaders could instead aspire to looser, wider connections across the company, and an intentional diminishing of downward control. These are the hallmarks of deep resilience.

This is a model, again, we can adopt from natural ecosystems: more weak ties, more incidental interactions, more resilience.

| Stowe Boyd

J. G. Ballard envisioned a different sort of rewilding:

Thirty years on, the future will still be boring. I see an endless suburbanization, interrupted by notes of totally unpredictable violence: the sniper outside the supermarket, the bomb outside suburban hypermarket, the madman with the Kalashnikov in McDonald’s. But this random violence is totally without connection to people’s everyday lives. This will lead to a feeling that the world is arbitrary and illogical, insane even. That’s a frightening kind of landscape.

| J. G. Ballard

Echolocation

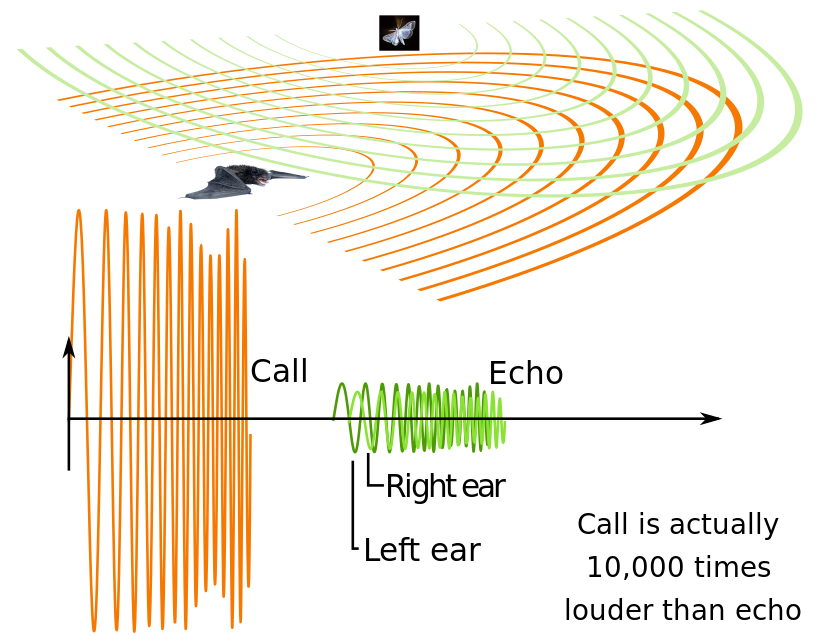

Not only bats and toothed cetaceans (whales and dolphins) use echolocation.

Two kinds of birds — Swiftlets and Oilbirds — have the ability to use echolocation to guide their flight in dark conditions, such as in caves. Here’s a Wikipedia entry about the swiftlet genus Aerodramus:

The genus Aerodramus was thought to be the only echolocating swiftlets. These birds use echolocation to locate their roost in dark caves. Unlike a bat's echolocation, Aerodramus swiftlets make clicking noises that are well within the human range of hearing. The clicks consist of two broad band pulses (3–10 kHz) separated by a slight pause (1–3 milliseconds). The interpulse periods (IPPs) are varied depending on the level of light; in darker situations the bird emits shorter IPPs, as obstacles become harder to see, and longer IPPs are observed when the bird nears the exit of the cave. This behavior is similar to that of bats as they approach targets. The birds also emit a series of low clicks followed by a call when approaching the nests; presumably to warn nearby birds out of their way. It is thought that the double clicks are used to discriminate between individual birds. Aerodramus sawtelli, the Atiu swiftlet, and Aerodramus maximus, the black-nest swiftlet are the only known species which emit single clicks. The single click is thought be used to avoid voice overlap during echolocation. The use of a single click might be associated with an evolutionary shift in eastern Pacific swiftlets; determining how many clicks the Marquesan swiftlet emits could shed light on this. It was also discovered that both the Atiu swiftlet[8] and the Papuan swiftlet[9] emit clicks while foraging outside at dusk; the latter possibly only in these circumstances, considering that it might not nest in caves at all. Such behavior is not known to occur in other species,[8] but quite possibly does, given that the Papuan and Atiu swiftlets are not closely related. However, it has recently been determined that the echolocation vocalizations do not agree with evolutionary relationship between swiftlet species as suggested by DNA sequence comparison.[10] This suggests that as in bats, echolocation sounds, once present, adapt rapidly and independently to the particular species' acoustic environment.

I never cease to be amazed at the wonders of the world.

Note that some blind people have developed a similar sort of echolocation, emitting clicks (or snapping their fingers) and listening for echoes all of which takes place in the audible range of human hearing.